In 2007-2008, Rob Leventhal, Associate Professor of German Studies, directed a Group Independent Study on the reemergence of the Jewish Community in Munich, Germany and the construction of the new Jewish Synagogue, Jewish Center, and Jewish Museum at St. Jakobsplatz. During the spring break of 2007, Leventhal and then W&M Students Sam Thacker, Olivia Lucas, Daniel Reisch, Benjamin Fontana, and K.C. Tydgat traveled to Munich with financial support of the Charles Center, the Reves Center, the Associate Provost of Research, and the Dean of Arts and Sciences, to study the Jewish Community and the new Jewish Center. Leventhal continued to work on the project, returning to Munich several times to conduct further interviews and do more research, and has now published “Community, Memory, and Shifting Jewish Identities: The Case of Munich, 1989 to the Present” in The Journal of Jewish Identities 4/1 (2011) 13-43.

The “negative symbiosis” of post-war German-Jewish culture took a decisive turn in 1989 with the fall of the Wall and the almost immediate unification of Germany one year later. Based as it was on a specifically German-Jewish perspective and orientation, this prevailing reading of the situation of the Jews in Germany underwent a radical change with the simultaneous dissolution of the Soviet Union, and the Federal Republic’s willingness to serve as a Zufluchtsort – a place of sanctuary – for over a quarter of a million Russian Jews over the next fifteen years. Munich became a destination of choice for many Russian Jewish émigrés, often even preferred to Israel and the United States. The utopistic promise of the reunification, the initial euphoria that followed 1990, the social welfare state of Germany, and the strength of the existing Jewish community in Munich all contributed to a powerful vision of future affluence, citizenship, cultural and social belonging and support that attracted thousands of Russian Jews to Munich.

By 1996-1997, however, this positive image of Germany and the optimistic sense of the Russian Jewish émigrés had changed radically. In a study published in 1999 based on data captured and analyzed in the preceding two years, the team of Julius Schoeps painted a very bleak picture indeed both of the current state of this community as well as its short and longer term prospects unless fundamental changes could be made, both by the Jewish Gemeinde, and the city, state and federal governments. Schoeps and his team pointed out that while fear of anti-Semitism had fallen since 1993-1996 (when it was at its height because of the vicious attacks against foreigners, mostly by Neo-Nazi groups in Mölln, Solingen, Hoyerswerda). There has been a dramatic increase in unemployment among the Russian Jewish émigrés, problems with integration into the work and housing market, insufficient and poor language instruction, increasing isolation and alienation, both from the existing Jewish Community and the German communities in which they were embedded, the sense of loss of both prior status and present perspective, feelings of dependence and hopelessness. Many respondents to the questionnaire the group developed indicated a kind of cultural collective depression.

The situation for Russian Jewish émigrés in the Federal Republic of Germany changed radically since 2000. Most importantly, significant changes in the Federal Law concerning immigration have all but cut off the flow of Jewish émigrés from the former Soviet States. According to the new procedures and regulations of the German Immigration Law, there are essentially three classes of Jewish émigrés from the former Soviet States: there are those who placed an application to enter Germany prior to July 1, 2001, those who placed their immigration application between the July 1, 2001 and December 12, 2004; and those who placed their Einreiseantrag after the 12th of December, 2004.

The possibility of admitting more Russian Jewish émigrés has now been directly linked to ability and willingness of the Länder to support the GemeindeGemeinde. For the period after 2006, while there have been many negotiations among the four parties directly involved – the Auswärtiges Amt, the BAMF, the Zentralrat der Juden in Deutschland, and the Union Progressiver Juden – and supposedly some oral “financial commitments” have been made, as of this writing no actual fundsGemeinde. For the year 2005, no applications or Anträge for entry into the Federal Republic were accepted: “Die deutschen Botschaften und Konsulate in den Ländern der ehemaligen Sovietunion haben nach Auslaufen des ‘Kontingentverfahrens’ am 31. Dezember 2004 schlichtweg keine Auswanderungsanträge mehr angenommen.”

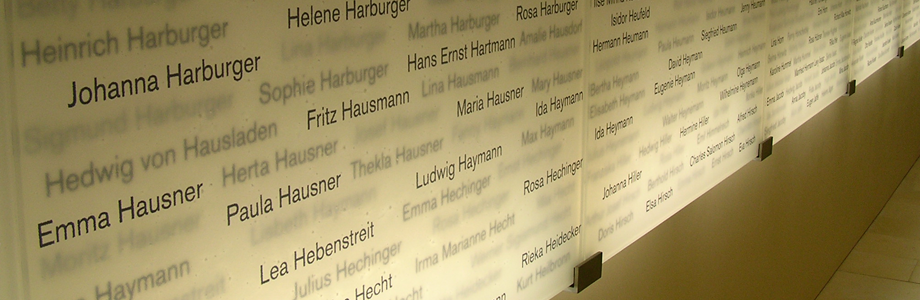

In 2003, on the 65th anniversary of Kristallnacht, then Federal President Johannes Rau helped lay the first stone of Jüdisches Zentrum Jakobsplatz – the Jewish Center at the Jakobsplatz – a massive architectural and cultural event that has now become the location for the new central Synagogue, the Jewish Museum of Munich, a Jewish Community Center, and a Jewish School. A plot to bomb the ceremony by members of a neo-nazi group was successfully thwarted. The Synagogue opened its doors on November 9, 2006, and the Jewish Museum was inaugurated on March 22, 2007. While some observers and critics claim that such physical demonstrations of culture merely “externalize” or “displace” the deeper cultural conflicts, and many German Jews remain highly skeptical of a “reemergence of Jewish culture,” it was necessary to work-through the various readings to arrive at a more objective, more historical, and therefore more encompassing sense of this transformation of Munich’s center.

Leventhal explored this significant reconstruction and reemergence in Munich with his students as a cultural and social event that is saturated with historical meaning and rife with conflicted and conflicting views, both for the German Jews and DPs of the first and second generation and the Russian Jewish émigrés who have arrived since 1989. Through close study of the literature and journalism, close tracking of the history of this emergence, on-site interviews with key literary, historical, and community figures, and real-time interpretive analysis of the structures themselves in their historical, social, and cultural contexts, the GIS (Group Independent Study) GRMN 411 attempted to a understand what was at stake in this reconstruction, how it has been and is still being interpreted and used, how it is functioning as a cultural-discursive event and site.